The Future of Futures

"Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it, and I shall move the world". This is the story of how humanity used financial leverage to change the world.

Ancient Risk Management

The concept of leverage stretches back thousands of years, emerging from humanity's fundamental need to manage uncertainty and risk.

4000 years ago, farmers in ancient Mesopotamia had a problem: how could they ensure the price of their crop today, when harvest season was 6 months away? Their solution: create tokens to represent future commodity deliveries. These tokens could be exchanged for gold, or other commodity tokens, creating the world's first futures market. Traders quickly realized that, unlike with bartering, they could speculate on the movement of prices for assets they didn't even own: they could sell assets they didn't have today, or buy more than they could afford, based on the promise of future delivery.

Leverage was born.

Even better, Aristotle later documented how the philosopher Thales used what he called a "financial device of universal application" to profit from olive harvest predictions. Thales used his knowledge of the stars (as good an investment strategy as any) to predict the following year’s olive harvest. He secured rights to olive presses during winter when demand was low, then rented them out at harvest time when demand spiked, essentially creating the first recorded options trade.

Japan's Revolutionary Approach

The world's first official futures exchange emerged in Japan, with the Dojima Rice Exchange in 1697. Rice was the foundation of Japan's entire economic system: land values, samurai payments, taxes, but most importantly SUSHI were all rice-based.

The Dojima Exchange introduced several concepts that continue to define modern leverage trading. Contracts were fungible (standardized and interchangeable), allowing them to be traded freely between multiple counterparties. The exchange also implemented margin requirements and daily settlement - innovations that wouldn't appear in Western markets for a century.

By the mid-18th century, futures trading volume exceeded the physical rice market: a sign of things to come.

The Chicago Revolution

Though it may be hard to believe, things were looking even bleaker in 19th Chicago than they do in the age of 'Chiraq'. The grain market was in chaos: farmers often burned grain for fuel rather than accept below-cost prices, while winter scarcity created consumer hardship.

Twenty-five Chicago businessmen established the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) in 1848 to address these issues.

The CBOT's solution - standardized "to arrive" contracts - allowed market participants to control large positions with relatively small capital outlays. A farmer could hedge an entire harvest with a fraction of its value, while speculators could amplify returns by trading contracts worth multiples of their invested capital. The CBOT remains a globally important exchange to this day.

The Financial Revolution: Beyond Commodities

The 1970s marked the futures market's expansion beyond its agricultural roots. When the Bretton Woods system collapsed in 1971, floating exchange rates created unprecedented currency volatility. The Chicago Mercantile Exchange launched the world's first financial futures in 1972: currency contracts that allowed traders to leverage foreign exchange movements.

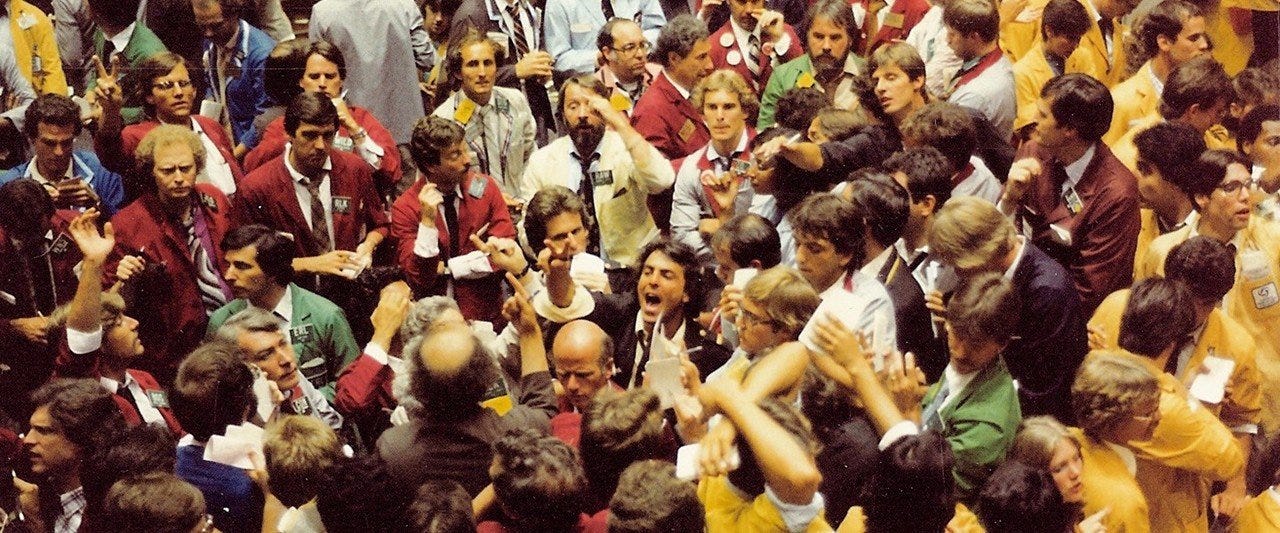

Interest rate futures followed in 1975, with Treasury bond futures becoming the world's most actively traded contracts by 1977. Those scenes of sweaty men in brightly-colored jackets started right about now.

Why Derivatives Dominate

Every mature market today has significantly more derivatives trading than spot trading, and this isn't coincidental - it's a mathematical inevitability. Leverage provides several crucial advantages:

Capital Efficiency: Traders can control large positions with minimal capital, freeing resources for other investments or risk management strategies. This is how hedge funds generate such massive returns: they lever their capital to take larger positions.

No Physical Delivery: Producers and consumers can hedge price exposure without tying up capital in physical inventory.

Price Discovery: Markets are a voting mechanism for the fair price of assets. Giving people the ability to vote with more than their bankroll lets them vote depending on their confidence level, which leads to more efficient price discovery.

A mathematical side-effect also emerged: the presence of expiry dates meant traders could make risk-free profits if contracts traded out of line with underlying assets. If the futures price moved above the spot price, traders could sell the future, buy the asset, and hold both until the future expired. This arbitrage mechanism keeps derivative prices aligned with spot markets.

Roll Risk and Fragmentation

However, traditional futures create new problems in modern markets. The vast majority of traders don't need their contracts to expire; they're trading for price exposure, not physical delivery. When I’m trading oil futures, I don’t want 20,000 barrels of crude at my doorstep.

Expiries creates four major inefficiencies:

Operational Burden: Traders must constantly "roll" positions from expiring contracts to new ones. This creates operational risk: many firms have accidentally taken delivery of commodities they never intended to own.

Transaction Costs: Every time traders roll their position, they pay exchange fees and market-maker spreads, creating hidden costs that compound over time.

Front-Running: Market makers can predict roll flows, creating invisible costs as they position ahead of predictable trading patterns. This was the basis of entire trading strategies that I created in my past life as an HFT trader.

Liquidity Fragmentation: Market makers have finite risk appetite, so listing correlated products across multiple order books decreases liquidity on each, increasing transaction costs for all but the most sophisticated traders.

The cost of rolling futures for market participants runs into many billions of dollars every year.

Perpetual Futures: The Evolution of Leverage

Cryptocurrency markets solved these problems with perpetual futures: contracts without expiry dates that maintain leverage benefits, while also eliminating roll costs. Instead of expiring, perpetual contracts use funding rates - periodic payments between long and short positions, that keep contract prices aligned with underlying assets. Perpetual futures, or “perps”, now make up over 95% of volumes in crypto markets.

This innovation represents leverage trading's natural evolution. Perpetual contracts provide continuous price exposure without operational complexity, transaction costs, or liquidity fragmentation of traditional futures. They offer pure leverage - the ability to amplify returns and manage risk, without the mechanical inefficiencies that plagued earlier systems.

Deploying more capital - steady lads (Do Kwon, 2022)

The Future of Leverage

From clay tokens to perpetual contracts, the history of leveraged trading is a story of innovation. Every stage of the journey has expanded leverage's benefits, while reducing its costs and complexities.

Today's perpetual futures represent leverage in its most refined form to date: continuous exposure, minimal costs, and maximum efficiency. As QFEX soldiers on with its mission to bring perpetual futures to traditional assets, we're witnessing the next chapter in leverage's 4,000-year evolution.